Reading Fluency Involves the 3 Components Known as:

What Is Fluency?

Fluency is the power to read "similar you speak." Hudson, Lane, and Pullen define fluency this style: "Reading fluency is fabricated up of at least three central elements: accurate reading of continued text at a conversational rate with advisable prosody or expression." Not-fluent readers suffer in at least ane of these aspects of reading: they make many mistakes, they read slowly, or they don't read with appropriate expression and phrasing.

Developing reading fluency with Read Naturally Strategy programs

Developing reading fluency with Read Naturally Strategy programs

Key Concepts

Why Is Fluency Important?

For many years, educators take recognized that fluency is an important aspect of reading. Reading researchers agree. Over 30 years of research indicates that fluency is 1 of the critical building blocks of reading, because fluency development is directly related to comprehension.

Here are the results of one study past Fuchs, Fuchs, Hosp, and Jenkins that shows how oral reading fluency correlates highly with reading comprehension.

| Measure | Validity Coefficients |

|---|---|

| Oral Recall/Retelling | .seventy |

| Cloze (fill in the bare) | .72 |

| Question Answering | .82 |

| Oral Reading Fluency | .91 |

To translate this type of correlation data, consider that a perfect match would be 1.0. Every bit you can run into, oral recall/retelling, fill in the blank, and question answering are all to a higher place 0.vi, which indicates there is a strong correlation. Only oral reading fluency is by far the strongest, with a .91 correlation.

Many researchers, including Breznitz, Armstrong, Knupp, Lesgold, and Pinnell, have found that fluency is highly correlated with reading comprehension—that is, when a student reads fluently, that student is likely to cover what he or she is reading.

Why are reading fluency and reading comprehension so highly correlated? Dr. S. Jay Samuels, a professor and researcher well known for his work in fluency, put forth a theory called the automaticity theory. According to Dr. Samuels, people have a express amount of mental energy. If you want to multitask or to become proficient at a complex task such every bit reading, you first demand to master the component tasks so y'all can do them automatically. For example, a reader who must focus his or her attending on decoding words may not accept enough mental energy left over to remember about the significant of the text. However, a fluent reader who can automatically decode the words tin can instead give full attention to comprehending the text. To become practiced readers, our students demand to become automatic with text so they can pay attending to the pregnant.

See besides:

- Determining who needs fluency educational activity

- Hasbrouck-Tindal oral reading fluency norms

- Video: Why reading fluency is of import

Challenges Faced by Not-Fluent Readers

Students get fluent by reading. Some students learn to read fluently without explicit instruction. For others, however, fluency doesn't develop in the class of normal classroom instruction.

Research analyzed by the National Reading Panel suggests that just encouraging students to read independently isn't the most effective way to better reading accomplishment. Too often, simply encouraging at-risk students to read doesn't result in increased reading on their part. During sustained silent reading, at-chance readers may get a book with mostly pictures and wait at the pictures, or they cull a difficult volume so they will expect like everyone else and and so pretend to read.

Even if at-hazard students practise read, they read more than slowly than the other students. In a 10-minute reading flow, a proficient reader who reads 200 words a minute silently could read two,000 words. In the same 10 minutes, an at-risk student who reads 50 words a minute would only read 500 words. This is equal reading time but certainly not an equal number of words read.

These students need to read more than, just only asking them to read on their own oft doesn't work. The National Reading Console has concluded that a more constructive class of activeness is for us to explicitly teach developing readers how to read fluently, pace past step.

Inquiry-Proven Fluency Strategies

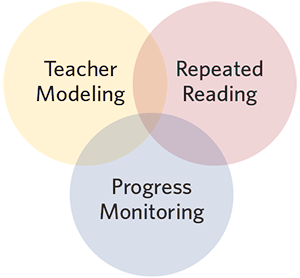

How do nosotros explicitly teach students to read fluently? The National Reading Panel found data supporting three strategies that improve fluency, comprehension, and reading achievement—teacher modeling, repeated reading, and progress monitoring.

Teacher Modeling

The first strategy is teacher modeling. Research demonstrates that various forms of modeling can ameliorate reading fluency. Examples of teacher modeling include:

- Teacher-assisted reading

- Peer-assisted reading

- Audio-assisted reading

Teacher modeling involves more than than just listening to someone else read. Students must be actively involved 100 percent of the time and in a multisensory way.

Teacher modeling teaches word recognition in a meaningful context, demonstrates right phrasing, and gives students practice tracking across the folio. A kid tin can benefit from teacher modeling in one case he or she knows at least 50 sight words and has a good sense of beginning sounds.

The reading charge per unit of the model reader is of import. Christopher Skinner, a reading researcher, plant that students who read lists of words with him slowly were more fluent with the words than students who read with him at a faster rate. The slower rate enables students to learn new words and analyze difficult words. As students larn more than words, they naturally become more fluent.

Another form of modeling is the neurological impress method. In the neurological impress method, a good and a struggling reader read together from a passage, with the more able reader reading near the rate of the struggling reader. Heckelman (1969) showed that after 29 fifteen-minute sessions, 24 seventh- through ninth-grade boys, who were an average of iii years behind in reading, gained an boilerplate of 1.9 years in reading based on the Oral Gilmore and the California Achievement Examination.

Repeated Reading

Some other technique that research has shown significantly builds reading fluency is repeated reading. In fact, the National Reading Panel says this is the most powerful way to improve reading fluency. This involves simply reading the same material over and over over again until accurate and expressive.

In the 1970s, LaBerge and Samuels studied what happens when students read passages over and again. They plant that when students reread passages, they got faster at reading the passages, understood them ameliorate, and were able to read subsequent passages ameliorate every bit a issue of the repeated reading.

Repeated reading is a form of mastery learning. The students read the aforementioned words so many times that they begin to know them and are able to place them in other text. Besides helping students bring words to mastery, repeated reading changes the fashion students view themselves in relation to the act of reading.

Progress Monitoring

People who play video games are presented with a specific goal and with firsthand, relevant feedback nigh their progress toward that goal. This combination of having a goal and getting feedback on progress can exist very motivating.

Progress monitoring takes reward of this combination to motivate students to read. You give students a specific, private reading goal, and you tell them exactly how you're going to know they've met information technology. Then, you give them the ways to measure how they're doing. Finally, you brand it unproblematic enough that they'll know they've met their goal even before you do. This progress monitoring is what motivates students to practice reading the same story over and over until achieving mastery.

Developing Reading Fluency With Read Naturally Strategy Programs

Developing Reading Fluency With Read Naturally Strategy Programs

The research-based Read Naturally Strategy combines these three strategies into highly constructive programs that accelerate reading achievement. Students become confident readers by developing fluency, phonics skills, comprehension, and vocabulary while reading leveled text. The time-tested intervention programs engage students with interesting nonfiction stories and yield powerful results.

Learn more nearly the Read Naturally Strategy

Learn more nearly the Read Naturally Strategy

Enquiry ground for the Read Naturally Strategy

Enquiry ground for the Read Naturally Strategy

The Read Naturally Strategy is bachelor in a diverseness of formats:

Choosing the right Read Naturally Strategy program

Choosing the right Read Naturally Strategy program

Bibliography

Armstrong, S. W. (1983). The effects of fabric difficulty upon learning disabled children'south oral reading and reading comprehension.Learning Disability Quarterly, vi, pp. 339–348.

Breznitz, Z. (1987). Increasing showtime graders' reading accurateness and comprehension by accelerating their reading rates.Journal of Educational Psychology, 79(three), pp. 236–242.

Fuchs, 50. S., Fuchs, D., Hosp, M. K., & Jenkins, J. R. (2001). Oral reading fluency as an indicator of reading competence: A theoretical, empirical, and historical analysis.Scientific Studies of Reading, v(3), pp. 239–256.

Heckelman, R. K. (1969). A neurological-impress method of remedial-reading instruction.Academic Therapy Quarterly, 5(4), pp. 277–282.

Hudson, R. F., H. B. Lane, and P. C. Pullen. (2005). Reading fluency cess and didactics: What, why, and how.Reading Instructor 58(eight), pp. 702-714.

Knupp, R. (1988). Improving oral reading skills of educationally handicapped simple school-aged students through repeated readings. Practicum paper, Nova University (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 297275).

LaBerge, D., & Samuels, Due south. J. (1974). Toward a theory of automatic data processing in reading.Cognitive Psychology, 6, pp. 292–323.

Lesgold, A., Resnick, L. B., & Hammond, Grand. (1985). Learning to read: A longitudinal written report of give-and-take skill development in two curricula. In Thou. Waller & Due east. MacKinon (eds.), Reading research: Advances in theory and practice. New York, NY: Academic Printing.

National Reading Panel. (2000).Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading educational activity. Washington, DC: National Plant of Child Wellness and Human Development.

Pinnell, G. S., Pikulski, J. J., Wixson, M. K., Campbell, J. R., Gough, P. B., & Beatty, A. Due south. (1995).Listening to children read aloud: Data from NAEP's integrated reading performance record (IRPR) at grade iv (NCES Publication 95-726). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Pedagogy, National Heart for Educational Statistics.

Samuels, Due south. J. (2002). Reading fluency: Its evolution and assessment. In A. E. Farstrup & South. J. Samuels (eds.), What research has to say well-nigh reading instruction, 3rd ed., pp. 166–183. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Samuels, Southward. J. (1997). The method of repeated readings.The Reading Teacher, 50(5), pp. 376–381.

Samuels, S. J. (2006). Towards a model of reading fluency. In South. J. Samuels and A. East. Farstrup (eds.), What research has to say well-nigh fluency educational activity. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Samuels, S. J. (1997). The method of repeated readings.The Reading Instructor, 50(5), pp. 376–381.

Skinner, C. H., Logan, P., Robinson, South. L., & Robinson, D. H. (1997). Demonstration as a reading intervention for exceptional learners.School Psychology Review, 26(three), pp. 437–447.

Source: https://www.readnaturally.com/research/5-components-of-reading/fluency

0 Response to "Reading Fluency Involves the 3 Components Known as:"

Post a Comment